AIDS is now “Stage 3 HIV Disease”

A deep dive into diagnostic standards—PCR for diagnosis, “immaculately infected” babies, and more

You might be surprised to find out that while we were distracted, the CDC quietly changed the term “AIDS” in its surveillance definition, to replace it with “stage 3 HIV disease.” (It’s certainly a good way to deal with the continuing problem of non HIV AIDS.) It gets significantly worse, though, when we look at the 2014 change to the case definition of “HIV disease,” which includes some very alarming changes in testing modalities that are, unsurprisingly, being sold as “more accurate” when in reality they are even more likely to induce false positives (assuming there are any true positives to begin with, which may be a stretch.) I know that this report is ten years old, but given that my book’s coverage of the “HIV” testing rubric is based on an earlier surveillance definition, I think that it is past time to cover it here. This will be long; bear with me or feel free to skip ahead.

I will first briefly discuss the conundrum of diagnosing infants. We will then move on to the changes that have been made to the case definition. The focus will move to the new testing modalities in two populations: either adults or infants whose mothers are uninfected, or infants whose mother’s status was positive or unknown, followed by a conclusion.

The 2014 change in the case definition of “HIV disease” classifies patients into Stage 0, 1, 2, or 3; this updated case definition remains the only recent update of significance regarding staging. I’d like to guide you to pay special attention to the testing rubrics, as well as how diagnoses are made in children under 18 months of age.

The Perth Group’s video is relevant here, especially for diagnosis of infants, although its implications reach much further. You can watch it by clicking the video link:

I would strongly encourage you to watch it before reading this. Here is the link to the article we will discuss, as well as an example of the type of language being used around “HIV infected infants.” We will move on to the report, mostly in its entirety, following this short excerpt. This phenomenon of “HIV infected” babies, some of whose mothers are “HIV negative,” may be an important key to unraveling this whole web.

The whole report can be found at the following link:

Revised Surveillance Case Definition for HIV Infection — United States, 2014

Here is the relevant section on infants with “perinatal exposure:”

In perinatally exposed children aged <18 months, antibody tests are not used to diagnose HIV infection because of the expectation that they might be false indicators of infection in the child due to passive transfer of maternal antibody. The HIV-1 NAT routinely used to diagnose HIV-1 infection in children of this age is likely to be negative in an HIV-2-infected child because it is insensitive to HIV-2. A positive HIV-2 NAT result would satisfy the criteria for a case. Otherwise, the diagnosis of HIV-2 infection in a child will need to wait until the child is aged 18 months, when it can be based on antibody test results.

An “NAT” is a nucleic acid test, usually PCR, so it is looking for fragments of DNA presumed to be associated with “HIV,” by the way. As you can see from the link in the previous sentence, this means “viral load.” This is a problem, because we know it is possible to have a positive (sometimes significant) viral load in the absence of any other indicators of “HIV.” We will address this further momentarily.

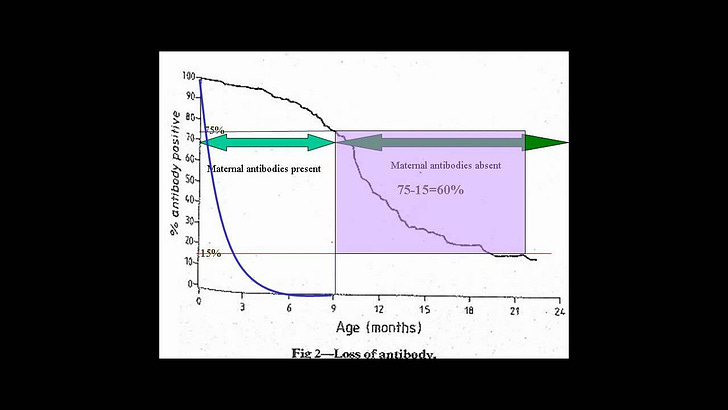

Also, after watching the video from the Perth Group linked above, I would ask why on earth does it take 18 months for antibodies inherited from the mother to disappear? I’ve never heard of maternal antibodies that lasted longer than a few months at best. What are these antibodies even reacting to?

Here is where we begin with the meat of this review. I’ll address changes in testing first, then circle back to the diagnosis of infants. As always, emphasis is mine throughout.

Following extensive consultation and peer review, CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists have revised and combined the surveillance case definitions for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection into a single case definition for persons of all ages (i.e., adults and adolescents aged ≥13 years and children aged <13 years). The revisions were made to address multiple issues, the most important of which was the need to adapt to recent changes in diagnostic criteria. Laboratory criteria for defining a confirmed case now accommodate new multitest algorithms, including criteria for differentiating between HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection and for recognizing early HIV infection. A confirmed case can be classified in one of five HIV infection stages (0, 1, 2, 3, or unknown); early infection, recognized by a negative HIV test within 6 months of HIV diagnosis, is classified as stage 0, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is classified as stage 3. Criteria for stage 3 have been simplified by eliminating the need to differentiate between definitive and presumptive diagnoses of opportunistic illnesses. Clinical (nonlaboratory) criteria for defining a case for surveillance purposes have been made more practical by eliminating the requirement for information about laboratory tests. The surveillance case definition is intended primarily for monitoring the HIV infection burden and planning for prevention and care on a population level, not as a basis for clinical decisions for individual patients. CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists recommend that all states and territories conduct case surveillance of HIV infection using this revised surveillance case definition.

Pardon the length of this block quote, but there are a few peculiarities that must be addressed. First of all, what are the multitest algorithms that have “improved” testing so much? And what are “HIV stages” 1 and 2? Only Stage 0, defined as having tested negative within six months of the positive test, and Stage 3, which used to be known as AIDS, are described in this document. Furthermore, a diagnosis of an opportunistic infection (OI) automatically classifies the patient as stage 3 unless they can be definitively placed in stage 0. From the section on staging: “The criteria for stage 0 consist of a sequence of discordant test results indicative of early HIV infection in which a negative or indeterminate result was within 180 days of a positive result. The criteria for stage 0 supersede and are independent of the criteria used for other stages.” This is interesting, as it allows for the possibility of being “newly infected” yet experiencing AIDS (or stage 3) defining illness, raising the question of whether the OI itself might cause the positive test result.

I like the addition of the “unknown” stage; we’re really covering all our bases here. Let’s consider the specific changes that have been made to testing.

The most important update is revision of the laboratory criteria for a confirmed case, which addresses the development of new diagnostic testing algorithms that do not use the Western blot or immunofluorescence HIV antibody assays.

[…]

In these multitest algorithms, "supplemental" HIV tests (for confirming or verifying the presence of HIV infection after a positive [or "reactive"] result from an initial HIV test) can now include antibody immunoassays formerly used only as initial tests (e.g., conventional immunoassays or rapid tests) or can include nucleic acid tests (NAT). The 2008 surveillance case definition was not clearly consistent with the new algorithms because it specified that a test used for confirmation must be a "supplemental HIV antibody test (e.g., Western blot or indirect immunofluorescence assay test)" (5). This revised surveillance case definition explicitly allows these new testing algorithms.

The Western Blot test has been out of use in Europe for at least two decades, at least partly due to its inconsistent results. Ten “protein bands” in the test were “associated with ‘HIV’,” although the criteria for a positive result ranged from 2 to 4 reactive bands, which were said to indicate antibodies reacting to those particular proteins. It also seems to me that the only real change of note is the addition of an NAT as a supplemental “confirmatory” test, when in the past antibody tests confirmed one another. Note that under these new guidelines, this is still a possibility.

Another important change is the addition of "stage 0" based on a sequence of negative and positive test results indicative of early HIV infection. This addition takes advantage of tests incorporated in the new algorithms that are more sensitive during early infection than previously used tests, and that together with a less sensitive antibody test, yield a combination of positive and negative results enabling diagnosis of acute (primary) HIV infection, which occurs before the antibody response has fully developed.

I’m not even going to comment on this. (Okay, I am, but briefly.) What is there to say? Tests that are too sensitive (hence yield more false positives) are combined with tests that are “less sensitive” (and thus yield more false negatives; and none of which has been verified against the presence of actual “HIV”) somehow magically coalesce to produce an accurate diagnosis? What is this voodoo?

Here is a breakdown of every change that was made in these 2014 guidelines:

Adds specific criteria for defining a case of HIV-2, which were not included in the 2008 case definition. The new definition incorporates criteria for HIV-2 infection used in a report of surveillance for HIV-2 infection and included in one of the new CLSI [Clinical Laboratory and Stndards Institute—Ed.] testing algorithms.

“HIV2” is the alleged “African strain” of “HIV,” which you may recall has been characterized as mainly being transmitted through vaginal sex. This is how the difference in “HIV” demographics is explained; this is the reason that the African epidemic is allegedly primarily heterosexual whereas, outside of Africa, it is mainly to be found among MSM. No explanation is posited as to how these epidemics have managed to remain largely isolated from one another over at least forty years. What a wily infectious pathogen; it’s so scary it doesn’t transmit between continents. In the interest of length, I will discuss “HIV2” in further detail in a later post.

Eliminates the requirement to indicate if opportunistic illnesses (AIDS-defining conditions) indicative of stage 3 (AIDS) were diagnosed by "definitive" or "presumptive" methods. This requirement has been impractical to implement because the criteria to distinguish between "definitive" and "presumptive" methods were not interpreted in a standard, uniform way by state and local surveillance programs.

So all this is saying is that in the past, OIs could be diagnosed clinically (presumptively) or via laboratory results (definitively), but that the physician was required to state which method was used. This requirement has been lifted, so we have even less information.

Classifies stages 1–3 of HIV infection on the basis of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count unless persons have had a stage-3–defining opportunistic illness. The CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage is used only when the corresponding CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is unknown. This avoids overestimating the proportion of cases in stage 3, which occured when the stage was based on whichever CD4+ T-lymphocyte test result (count or percentage) indicated the more advanced stage. Clinical evidence suggests the percentage has little effect on prognosis after adjusting for the count.

What is interesting about this is not the change in modality, but the elimination of the term “AIDS” in favor of “stage 3 ‘HIV’ disease.” Again, it would be nice to know actual T cell counts for each stage, but what we do notice is that the presence of a “stage 3 defining OI” automatically places an individual in Stage 3, unless they’re at Stage 0, as we saw above. It’s confusing me too.

Removes the requirement that a "physician-documented" diagnosis must be based on laboratory evidence. This revision allows clinical evidence to be sufficient to define a case when it is impractical to retrieve laboratory test information regarding the initial diagnosis. The new definition also clarifies that the date of a physician-documented diagnosis is the diagnosis date recorded in a medical record note, rather than the date that the physician wrote the note.

Again, we’re moving away from laboratory results and toward more clinical diagnoses, reminiscent of the Bangui definition that is still in place today in some parts of Africa. Here is more about diagnosis of children:

Eliminates the requirement that evidence of HIV infection in a child's biologic mother is needed to define a case of HIV infection in a child aged <18 months when laboratory testing of the infant independently confirms HIV infection. This change was recommended in a position statement approved at the June 2009 annual meeting of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) (13).

This is incredibly significant. For a baby to be diagnosed as confirmed “HIV” positive, there is no longer any need to ascertain the status of the mother; indeed, as we will see later, the mother can even be “HIV” negative and the baby can get a diagnosis. Where are all these immaculate infections coming from? Here’s the last change we will address:

Extends the use of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and percentages for determining the stage of HIV infection to children as well as adults and adolescents, and now determines the stage in children aged 6–12 years the same way as in adults and adolescents. In the 2008 case definition, only the presence or absence of opportunistic illnesses was used as criteria for staging cases among children aged <13 years.

It used to be the case that a child would need to have clinical evidence of an OI to qualify for a “stage 3” (AIDS—what is with this constant morphing of language? Is the intent to confuse?); now, they can be diagnosed on only a T cell count and no disease whatsoever. One thing I find rather perplexing about these guidelines is that they seem to simultaneously be promoting diagnosis without testing as well as expanding the scope of testing modalities to include some (NAT or “viral load”) that are wildly over sensitive. It’s almost like they don’t know what in the heck they’re doing over at the CDC.

The remainder of these changes are not worthy of comment, so I will state them here without discussion, in the interest of length but also completeness. They “Combine the adult and pediatric criteria for a confirmed case of HIV infection and specifies different criteria for staging HIV infection among three age groups (<1 year, 1–5 years, and ≥6 years); Eliminate the distinction between definitive and presumptive diagnoses of HIV infection in children aged <18 months; Remove lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia) from the list of opportunistic illnesses indicative of stage 3 in children because this illness is associated with moderate rather than severe immunodeficiency.”

This is already long, so we will consider criteria for “confirming a case” in adults and children briefly. The first section refers to patients over 18 months or under 18 months whose mothers were not infected.

For a confirmed positive result, the following criteria must be met—please pardon the length, but this is important:

A multitest algorithm consisting of

— A positive (reactive) result from an initial HIV antibody or combination antigen/antibody test, and

— An accompanying or subsequent positive result from a supplemental HIV test different from the initial testThe initial HIV antibody or antigen/antibody test and the supplemental HIV test that is used to verify the result from the initial test can be of any type used as an aid to diagnose HIV infection. For surveillance purposes, supplemental tests can include some not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for diagnosis (e.g., HIV-1 viral load test, HIV-2 Western blot/immunoblot antibody test, and HIV-2 NAT). However, the initial and supplemental tests must be "orthogonal" (i.e., have different antigenic constituents or use different principles) to minimize the possibility of concurrent nonspecific reactivity. Because the antigenic constituents and test principles are proprietary information that might not be publicly available for some tests, tests will be assumed to be orthogonal if they are of different types. For example:

— One test is a combination antigen/antibody test and the other an antibody-only test.

— One test is an antibody test and the other a NAT.

— One test is a rapid immunoassay (a single-use analytical device that produces results in <30 minutes) and the other a conventional immunoassay.

— One test is able to differentiate between HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies and the other is not.

Tests also will be assumed to be orthogonal if they are of the same type (e.g., two conventional immunoassays) but made by different manufacturers. The type of HIV antibody test that verifies the initial test might be one formerly used only as an initial test (e.g., conventional or rapid immunoassay, HIV-1/2 type-differentiating immunoassay), or it might be one traditionally used as a supplemental test for confirmation (e.g., Western blot, immunofluorescence assay).

It looks like there are a plethora of ways to “diagnose” “HIV” infection. If an antibody test paired with an antigen/antibody test fails to yield a positive, use the NAT (“viral load”) to confirm. If that fails, compare “HIV1” and “HIV2.” That last one is wild because “HIV” is admitted by the mainstream to be a “quasispecies,” so having two such entirely different subtypes is somewhat suspect. The only requirement is that the two tests used be “orthogonal;” that is, “[having] different antigenic constituents or [using] different principles,” OR being made by different manufacturers. This loophole continues to allow for diagnosis based on antibody tests confirming one another, as has always been the case and has been heavily criticized as a practice. It’s amazing to me how these 2014 guidelines are being sold as “far more accurate” than previous guidelines and definitions of cases, when in fact the guidelines allow for the exact same testing rubric in some cases. In cases where “viral load” is included in diagnosis, these guidelines actually make things worse in terms of false positives. Indeed, consider the following criteria for positivity—a positive result can potentially be based only on nucleic acid testing:

A positive result or report of a detectable quantity (i.e., within the established limits of the laboratory test) from any of the following HIV virologic (i.e., nonantibody) tests:

— Qualitative HIV NAT (DNA or RNA)

— Quantitative HIV NAT (viral load assay)

— HIV-1 p24 antigen test

— HIV isolation (viral culture) or

— HIV nucleotide sequence (genotype).

The last method of confirming positivity is as follows:

Any positive result of a multitest HIV antibody algorithm from which only the final result was reported, including a single positive result on a test used only as a supplemental test (e.g., HIV Western blot, immunofluorescence assay) or on a test that might be used as either an initial test or a supplemental test (e.g., HIV-1/2 type-differentiating rapid antibody immunoassay) when it might reasonably be assumed to have been used as a supplemental test (e.g., because the algorithm customarily used by the reporting laboratory is known).

So this basically eliminates the need for proof of confirmatory testing. The report moves on to discuss clinical evidence for diagnosis. These clinical criteria are not difficult to meet. They are found to be met by the combination of:

A note in a medical record by a physician or other qualified medical-care provider that states that the patient has HIV infection, and

One or both of the following:

— The laboratory criteria for a case were met based on tests done after the physician's note was written (validating the note retrospectively).

— Presumptive evidence of HIV infection (e.g., receipt of HIV antiretroviral therapy or prophylaxis for an opportunistic infection), an otherwise unexplained low CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, or an otherwise unexplained diagnosis of an opportunistic illness.

Now one can qualify as a “case” if one exhibits low T cell counts, opportunistic infections, and even if they have received antiretroviral therapy. I assume that with the recent explosion of PrEP propaganda, there must be some caveat to account for those individuals who are receiving ARVs.

The final section we will examine focuses on infants less than 18 months of age whose mothers either were known to be infected or whose status was unknown. This should be interesting, considering the dramatic variability of antibody persistence after birth. All of the following criteria must be met to determine a “case:”

Positive results on at least one specimen (not including cord blood) from any of following HIV virologic tests:

— HIV-1 NAT (DNA or RNA)

— HIV-1 p24 antigen test, including neutralization assay for a child aged >1 month

— HIV isolation (viral culture) or

— HIV nucleotide sequence (genotype).The test date (at least the month and year) is known.

One or both of the following:

— Confirmation of the first positive result by another positive result on one of the above virologic tests from a specimen obtained on a different date or

— No subsequent negative result on an HIV antibody test, and no subsequent negative result on an HIV NAT before age 18 months.

In the absence of laboratory test results, the following clinical criteria are sufficient for diagnosis:

The same criteria as in section 1.1.2 (refer to the criteria above for clinical evidence in adults—ed) or

All three of the following alternative criteria:

— Evidence of perinatal exposure to HIV infection before age 18 months

A mother with documented HIV infection or

A confirmed positive test for HIV antibody (e.g., a positive initial antibody test or antigen/antibody test, confirmed by a supplemental antibody test) and a mother whose infection status is unknown or undocumented.

— Diagnosis of an opportunistic illness indicative of stage 3 (Appendix).

— No subsequent negative result on an HIV antibody test.

We can see clearly that antibody tests are not typically used in infants whose mothers were not known to be “HIV” negative; rather, “viral load” can be used, as well as detection of p24 antigen (which Montagnier famously stated was not specific to “HIV”), or even “viral isolation,” which is hilarious because they immediately add the parenthetical that they really mean “culture.” Culture is a far cry for true isolation.

Finally, we come to criteria to determine if the child is uninfected.

A child aged <18 months who was born to an HIV-infected mother or had a positive HIV antibody test result is classified for surveillance purposes as not infected with HIV if all three of the following criteria are met:

Laboratory criteria for HIV infection are not met

No diagnosis of a stage-3-defining opportunistic illness (Appendix) attributed to HIV infection and

Either laboratory or clinical evidence of absence of HIV infection as described:

No positive HIV NAT (RNA or DNA) and at least one of the following criteria:

— At least two negative HIV NATs from specimens obtained on different dates, both of which were at age ≥1 month and one of which was at age ≥4 months.

— At least two negative HIV antibody tests from specimens obtained on different dates at age ≥6 months.

The baby can therefore be definitely negative following a positive test. There is also a long section on determining “presumptive” lack of infection as well as “indeterminate” status. This all seems like a very complicated way of saying they don’t know what on earth they’re doing trying to diagnose babies, particularly when the understanding of the mode of “infection” remains murky. One criterion I noticed for “clinical evidence” is interesting: “A note in a medical record by a physician or other qualified medical-care provider states that the patient is not infected with HIV.” So providers get to just state this with no supporting evidence? This shouldn’t surprise us, I suppose.

The document also covers diagnosis of “HIV2” and discusses staging, but this is already long enough and tells us everything we need to know about the current state of “HIV” diagnosis and surveillance in this country, so I will stop here. To summarize:

AIDS is no longer AIDS, at least for surveillance purposes; it is now “Stage 3 HIV disease.” We have, quite literally, come full circle with this circular (ha!) definition and non-HIV AIDS is thus cleverly hidden in plain sight.

Antibody tests can still be “confirmed” by other antibody tests, so long as their manufacturers are different. (This leads to some interesting questions about the replicability of these tests.)

“Viral load” can now be used for diagnosis. In particular, for babies that seem to have “immaculate” infections, this test is encouraged.

There remains a lot of wiggle room for physicians to simply state that a patient is positive or negative, which has concerning implications regarding diagnosis based on risk group membership.

No one knows what a positive antibody response really means in a baby, and, as the Perth group indicated, this should cast suspicion on what a positive antibody test means for anyone.

If you’ve made it to the end, you’re very persistent. As always, let me know any questions or comments below.

All I can say is that if 'HIV' testing was a mess in the past, it's now utter chaos. All the problems the PG have documented with the Western Blot and ELIZA are all still there, and now we have more criteria thrown into the mix. And yes, using one antibody test compared to another one from a different manufacturer is absolutely hilarious. All of this screams of a medical system doing everything it can to keep 'HIV disease' alive and well via obfuscation.

"HIV disease" is boggling my mind. I guess it saves the awkwardness of saying "may lead to AIDS"