Tuskegee Whistleblower Peter Buxtun Dies at 86

Buxtun ended “the most notorious medical research scandal in US history”

Peter Buxtun, whose years-long efforts finally succeeded in ending the infamous Tuskegee Study—“Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro” (1)—has died at age 86.

“Buxtun is revered as a hero to public health scholars and ethicists for his role in bringing to light the most notorious medical research scandal in U.S. history,” the Associated Press reported July 16. “Documents that Buxtun provided to the Associated Press (AP), and its subsequent investigation and reporting, led to a public outcry that ended the study in 1972.” (2)

The Tuskegee Study began in 1932, when the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) collaborated with the Tuskegee Institute (in Macon, AL) to study the long-term effects of untreated syphilis in Black men. At that time, there was no cure for syphilis and only a few, questionably effective, treatments. The 399 Alabama sharecroppers with syphilis who were recruited for the study were told only that they had “bad blood”; they weren’t told they had a transmissible, progressively debilitating disease. Two hundred Black men who didn’t have syphilis were selected as a control group. For their participation, each of the men was given free “medical care” consisting mostly of aspirin, plus burial insurance. (3)

For the next 40 years, the men were observed, prodded, measured and X-rayed as their disease progressed from lesions and flu-like symptoms to damage in their brains, hearts, eyes, and nervous systems and, too often, led to premature death. (4)

In 1943, the new drug penicillin became the “treatment of choice” for syphilis, but the sick men in the study weren’t treated. For another 30 years, they continued to be observed by the USPHS—and later, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)—without treatment as their disease progressed. (3)

In 1937’s Nazi-occupied Prague, Peter Buxtun was born to a Jewish father and Catholic mother. Peter’s father urged family and friends to leave Czechoslovakia while they could, and in 1939, the family emigrated to the United States, settling in rural Oregon. After graduating from the University of Oregon and serving in the US Army as a combat medic, Peter joined the USPHS in 1965. While working as a federal public health employee in San Francisco, Peter overheard a colleague mention the Tuskegee Study.

Peter was insatiably curious and soon located the papers describing the study, which was conducted quite publicly—a follow-up research report was published in a scientific journal every few years. As a former medic and current public health worker, Peter knew syphilis was easily cured with penicillin. As a child, Peter had absorbed his father’s stories describing the Nazi horrors they’d escaped, and to him, the Tuskegee Study resembled them all too closely. In 1966, he wrote to the CDC in Atlanta, outlining his concerns about the study and comparing it to the medical experiments the Nazis performed on Jews, gay men, the Roma, and other perceived enemies. In 1967, Peter was rewarded with a summons to Atlanta, where he was admonished by his boss’s bosses and told to go back to work and stop making trouble. That was not in Peter’s nature.

“Repeatedly, agency leaders rejected his complaints and his call for the men in Tuskegee to be treated,” the AP reported. (2)

Peter soon left the USPHS for law school but the Tuskegee Study still gnawed at his conscience. He gave his Tuskegee Study documents to a friend, AP reporter Edith Lederer. In July 1972, AP investigative reporter Jean Heller wrote the story that blew the scandal wide open.

I was a college student in the wildly contentious summer of 1972 and when I heard a radio report about the Tuskegee Study, it felt like a punch to the gut. In the wake of the leaked Pentagon Papers, raucous and sometimes violent anti-Vietnam war protests, the stench of corruption leaking from the Nixon White House, and the summer school craziness of 8am physics followed by hours in a sweltering hamburger joint, I filed the study away in my memory and flipped burgers.

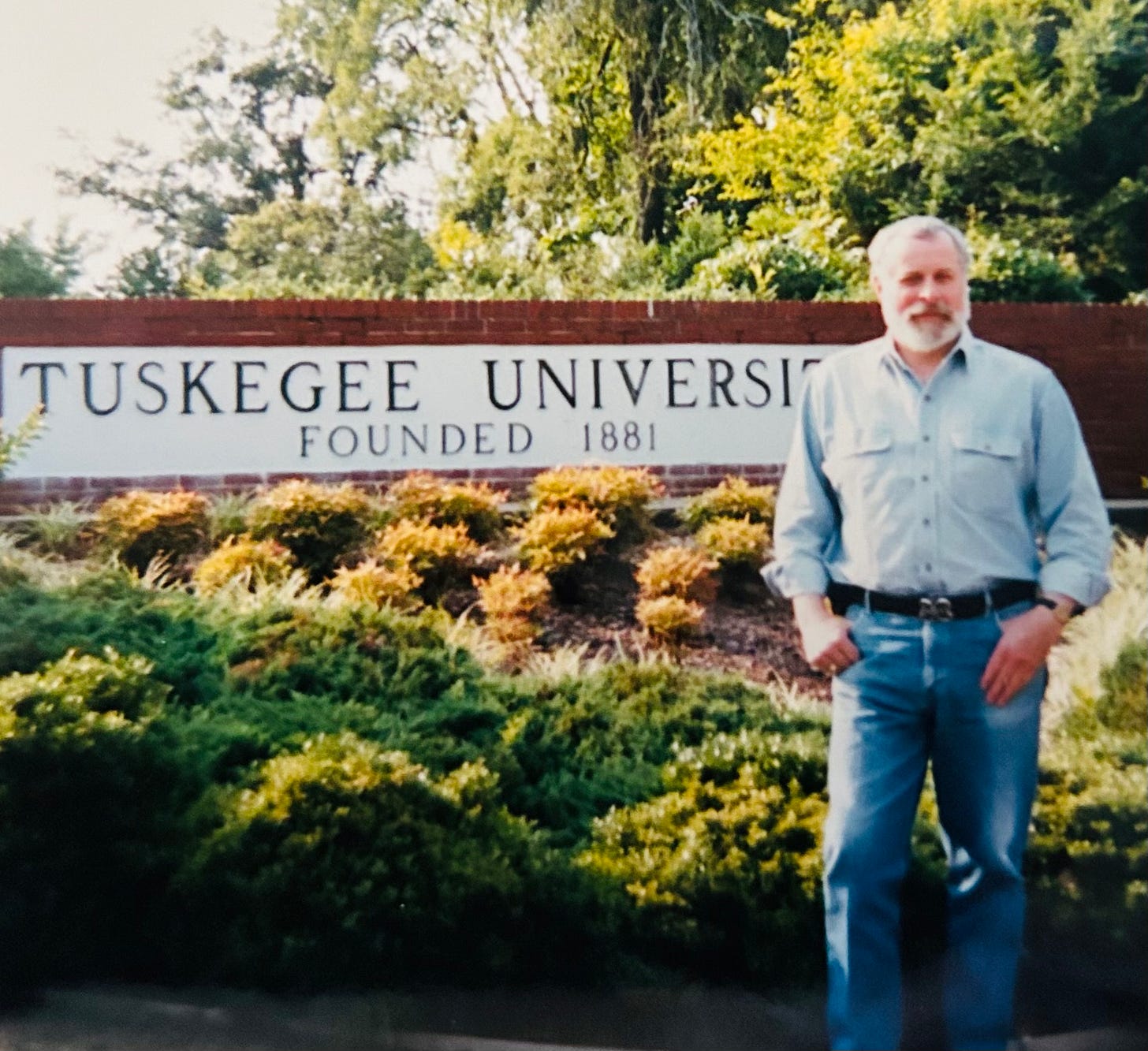

Twenty-some years later, I met Peter Buxtun as the 20th anniversary of the Tuskegee Study’s closure was commemorated. For a book project that never materialized, I accompanied him to Alabama in summer 1994. We visited Tuskegee University, meeting teachers and students and enjoying a locally sourced lunch prepared by student gardener/chefs.

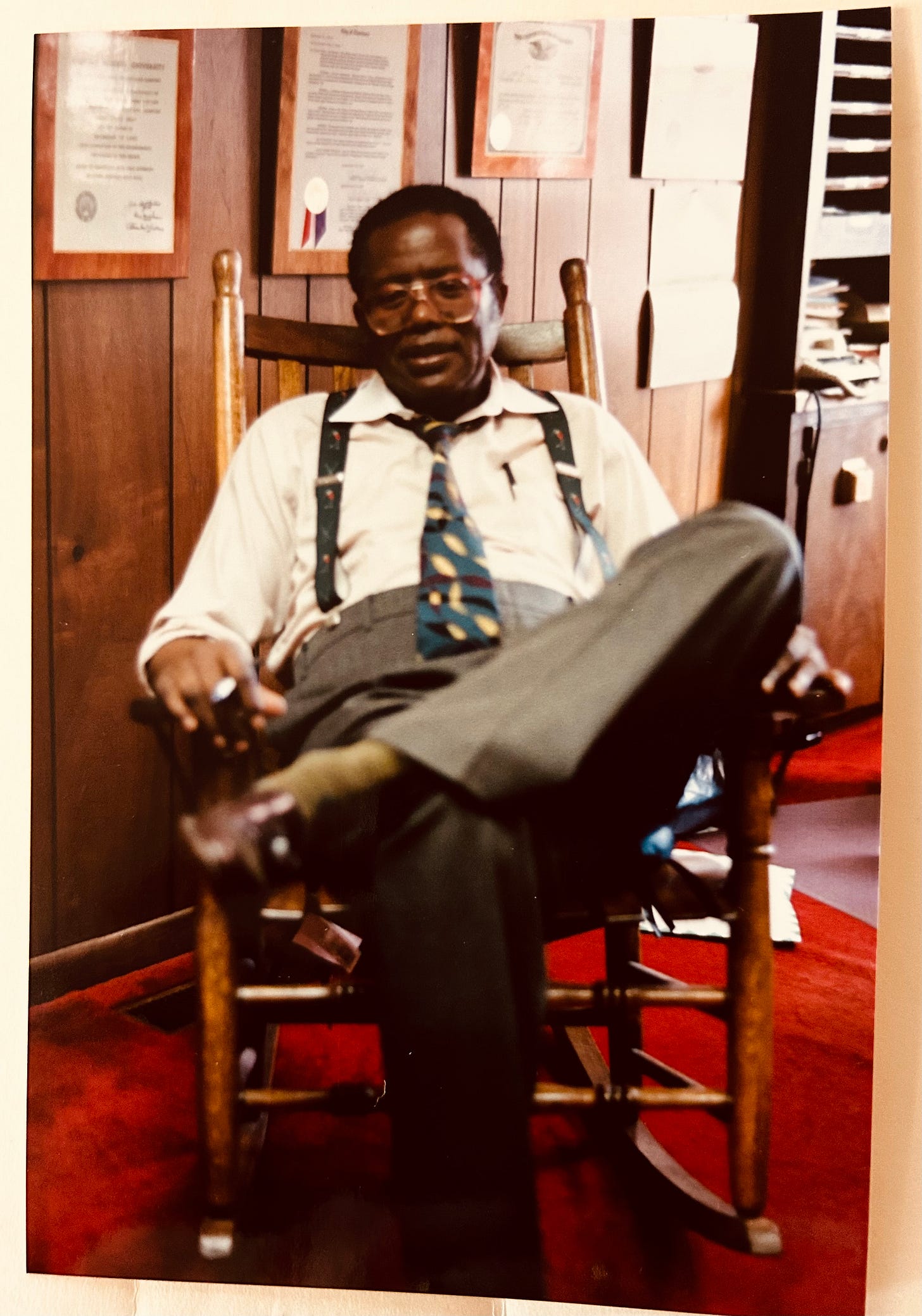

In Tuskegee proper was the office of Fred Gray, attorney for survivors of the Tuskegee Study. Mr. Gray’s 1972 lawsuit—settled out of court in 1973 for $10M—not only obtained lifelong healthcare for the 72 Tuskegee Study survivors and many families, but also resulted in the Department of Health and Human Services requiring informed consent for all studies with human subjects.

Already a well-known civil rights attorney in 1972, Mr. Gray had represented Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and the marchers injured on “Bloody Sunday” at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In 1994, Mr. Gray showed us around his office, including a room with a long picnic table overflowing with legal files. “The Tuskegee Study was my largest case when I opened my office in 1973,” he said, “and guess what’s my biggest case today? The Tuskegee Study.”

On May 16, 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal Presidential Apology for the study.

And while Peter attended the White House reception accompanying President Clinton’s apology, he was always reluctant to accept praise or even credit for his part in ending the Tuskegee Study. Peter rejected the designation of “whistleblower,” because research reports describing the study had been publicly available for decades before he discovered them. Peter felt, I think, that he shouldn’t be praised for doing his duty; when he saw impoverished men being refused the cure for a deadly disease under the auspices of the federal government, he was obligated at least to try to end their suffering. He struggled for seven years to make it happen, never faltering in his intention, never giving up, but also never really accepting credit for what he had accomplished.

A friend of a friend when I met him, Peter entertained us with stories of his travels around the world, the antiques (mostly guns) he loved searching for, and whatever random news story caught his attention that day. Peter was generous and adventurous and endlessly inquisitive, a student of history and art and a patron of exquisite restaurants in every city he visited. He was blithely eccentric. Peter was fun.

Rest in peace.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: An excellent book about the Tuskegee Study is Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment by James H. Jones. I highly recommend it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Vonderlehr, R.A., Clark, T., Wenger, O.C., Heller, J.R. “Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro.” Journal of Venereal Disease Information. 17:260-265, 1936.

2. “Tuskegee Syphilis Study Whistleblower Peter Buxtun Has Died at Age 86

— Buxtun is revered as a hero to public health scholars and ethicists.” Associated Press, July 16, 2024. https://www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/ethics/111108

3. “The Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee Timeline.” The U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

4. “Syphilis.” Cleveland Clinic. Last reviewed 12/27/2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4622-syphilis

At this point, knowing that the scientific data doesn't support the bacterial contagion and infection hypothesis, we'd have to go back and try to determine the actual cause that made those men sick.

That would in no way minimize the scandal, but might, instead, add another layer of scandal if it were determined that these men were exposed to some type of man-made environmental pollutant similar to toxic pesticide exposure causing symptoms the medical establishment labeled as "polio."

It's a peculiar scandal given the fact that syphilis is not caused by a microbe and the symptoms are not contagious. So, really, it was their INTENTION that was scandalous. They "believed" the symptoms known as syphilis were caused by a contagious microbe, and if left untreated (which would be best), would lead to death.

Note: The scandal was that the doctors ALLOWED the "syphilitic" men to exist untreated, but most pundits & people seem to think the men were INJECTED with syphilis.

In all likelihood most of the men were diagnosed by blood tests rather than clinical symptoms.

For decades in the USA you could not get married without taking a test for syphilis. Given that syphilis is not actually contagious, and no such microbe as the cause even exists, how many relationships were ruined by false positives for syphilis? How many virgins were accused of being syphilitic? "But I've never had sex before!" -- "You LIAR! The science says you're DISEASED! Get outta my site you WHORE!"

The bigger scandal of the 20th century was the HIV/AIDS/AZT scamdemic -- and it still exists. People with no symptoms are still testing positive for HIV and then being urged to consume unnecessary synthetic chemicals in order to "manage" their infection.

As for those who were diagnosed with HIV in the 1980s & 90s -- you can take the official stats for how many MILLIONS of humans, from babies to the elderly, said to have died from HIV/AIDS were actually MURDERED by the treatments for a virus that did not exist.

Many people who tested positive for HIV were asymptomatic, and after starting treatment, began showing symptoms that were said to have been caused by the nonexistent virus. They usually died slow, miserable, humiliating deaths from allopathic poisoning. The beautiful and extraordinarily talented Freddie Mercury was one of them. And Rock Hudson. Tricked into slow suicide by poison. Appalling. Heartbreaking. And it's still going on today but to a less dramatic extent. The poisons the people consume today for HIV take longer to kill a person. Eazy-E from NWA died within 1 month of taking AZT.